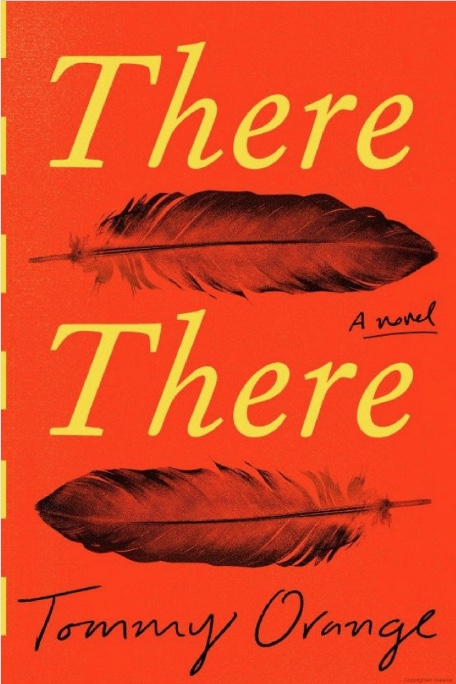

Karen’s Pick

August 2018

There There

Tommy Orange

Knopf June 5,2018

There There is a powerful and gritty first novel by Tommy Orange, a registered Cheyenne and Arapaho Native American. The title is borrowed from Gertrude Steins famous quote about Oakland, California, “There is no there there.”

This book is an all-too-real work of fiction. It is intended for the reader who would rather not be reminded of the results of poverty, racism, and alcoholism on today’s Native American. Orange offers a lengthy prologue that unapologetically confronts the reader with the backstory of the American Indian. He writes of the first Thanksgiving and those following when colonists poisoned the natives while dining at their tables; soldiers set villages on fire and performed acts of genocide and infanticide to eradicate native communities. These horrific deeds were commonly referred to as “successful massacres” by triumphant perpetrators. Orange submits, “The bullets were premonitions, ghosts from dreams of a hard fast future.” We are also asked to recollect the annihilation that took place on native lands as part of the Indian Relocation Act; a part of the Indian Termination Policy that attempted to assimilate Indians into cities so they would soon look and act like the white inhabitants – the process of Urbanity.

This is where the novel There There begins. Orange introduces us to the twelve main characters in the “story.” They are middle-aged women and men, young girls and adolescent boys, elders, all Native Americans who are trying to make sense of their lives in the 1970’s while living in Oakland, California. In this book, they are referred to as the Urban Indian.

The reader soon realizes while Orange refers to the beauty of Indian lore, there is very little joy, love or humor embodied in any of his characters. He introduces us to Tony Loneman, a young man with Fetal Alcohol syndrome, Dene Oxendene, who is struggling to become a documentarian, sisters Jacquie Red Feather and Opal Viola Victoria Bear Shield who, with their homeless family, occupied Alcatraz to protest the plight of the Urban Indian. We also “meet” Blue, a youth service coordinator, a battered wife, and Jacquie Red Feather’s daughter adopted into a white home. Bill Davis, a felon and now janitor at the Oakland Coliseum, and teenage brothers Orvil, Lony, and Loother are actively questioning what it means to be Indian.

The complex stories of these characters test our memory. Initially Orange assigns one chapter to each individual and then begins to weave relationships of other characters into their lives in subsequent chapters. Orange uses this method of character development to eventually inform us that all of his Urban Indians lives will intersect at the Big Oakland Powwow held at the Oakland Coliseum. The reader often feels empathy with the characters that will bring to the Powwow their collective angst, tragedy, loss, loneliness, and their own indomitable reasons for being “there.” However, it is young Orvil Redfeather, who is searching for his native roots, that provides a powerful meaning to the Powwow.

Orange writes of Orvil’s experience:

He is surrounded by the variegation of color and patterns specific to Indianess, gradients from one color to the next, geometrically sequenced sequined shapes on shiny and leathered fabrics, the quill, bead, ribbon, plume, and feathers from magpies, hawks, crows, and eagles…. To dance as if time only mattered insofar as you could keep a beat to it, in order to dance in such a way that time itself discontinued, disappeared, ran out, or into the feeling of nothingness under your feet you jumped, when you dipped your shoulders like you were trying to dodge the very air you were suspended in, your feathers a flutter of echoes centuries old, your whole being a kind of flight.

Orange offers further insight into the “why” of the Powwow and his Urban Indians’ state of being. He quotes from writer James Baldwin’s, Stranger in the Village, “People are trapped in history, and history is trapped in them.”

For this reader the surprisingly abrupt ending of There There was a relief. The time spent with the battered, broken and diminished characters was often difficult especially since their ability to endure was as close to a triumph as they would ever get. However, I believe it was the author’s intent to intentionally try to make the reader feel uncomfortable while reading about plight of the Urban Indian and what it means to be Native American in contemporary society.

Tommy Orange is a descriptive writer, whose stream of consciousness style is at times challenging. His characters are flawed, and his story is troublingly.

As another reviewer recently wrote,

This book will make you sad – read it anyway.

This book will make you mad – read it anyway.

This book will remind you of the lies we were taught as children – read it to remember.

I highly recommend reading There There. You just need to!