Lois’s Pick:

June, 2014

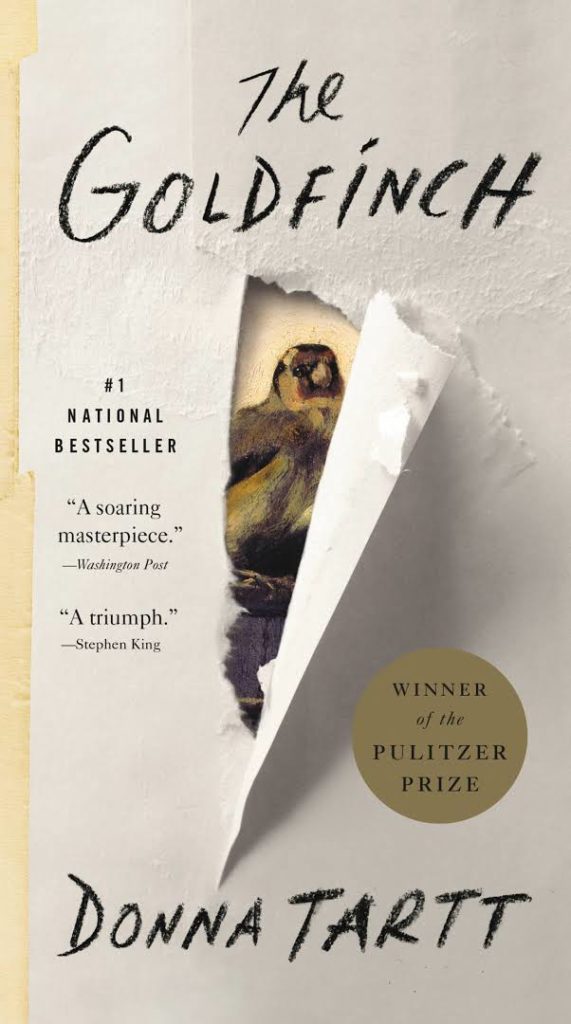

The Goldfinch

Donna Tartt, Published October 2014

Aspiring readers, do not be daunted by the length of this book. At almost 800 pages, it is well worth the read, for the story it tells, the characters that populate it, and the moods it evokes. This Pulitzer Prize winning novel has, as its central event, a terrorist attack on the Museum of Metropolitan Art in New York City. Our adolescent protagonist, Theodore “Theo” Decker is with his beloved mother on their way to school to discuss his recent suspension. They duck into the museum to escape the rain when a bomb explodes in the gallery they are walking through. Theo awakens in the rubble among the injured and dying. Frightened and dazed, he picks his way through the devastation. As he is leaving, he is stopped by a dying man and given a small signet ring for safekeeping; the man also points to the small picture that wasTheo’s mother’s favorite, Carel Fabritius’ The Goldfinch, which has been knocked from the wall but is miraculously intact. Theo takes the ring and the painting as he leaves the museum. When his mother does not return to their apartment, you experience with Theo the anxiety, the dread, and finally, the grief of her death. Tartt writes vividly and movingly of grief and of the unmooring it brings, particularly for a child. All that Theo is and much that he will become stems from his grief and from the memory of his mother.

The whereabouts of Theo’s father are temporarily unclear, as he has vanished from the life of his wife and child. Theo is taken in by the posh family of a school acquaintance. He is consumed by his memories of his mother, but also by the small picture he so diligently safeguards, never revealing its existence to another soul. He follows the clues given to him by the owner of the signet ring and in doing so, meets Hobie, a furniture restorer who will become an enduring friend.

His father, an alcoholic and compulsive gambler, eventually claims him and takes him to Las Vegas, which furthers his grief by disconnecting him from all that he has known. The portrait of the Las Vegas exurbs is vividly drawn—empty tract homes slowly being reclaimed by the desert. With no adult supervision, Theo is left to his own devices and in charge of a tiny neglected dog, Popper. He soon takes up with Boris Pavilkovsky, a classmate. Their teenage days are spent aimlessly, often fueled by beer and marijuana. Thanks to the shenanigans of Theo’s Dad, they are introduced to the Russian mob. It is during this interlude that the magnitude of Theo’s loss is clearest, at least to the reader.

Theo eventually makes his way back to New York with his treasured painting and Popper, settling in with Hobie to begin life as a young man in New York City. But he is still haunted by the memory of his mother and his choices are circumscribed by his sorrow.

Occasionally, the coincidences in this book seemed too extreme and the tremendous detail provided about furniture restoration, while interesting, could have benefitted from some editing. On the whole though, this was a wistful book that made me think about what might have been.